Coolidge’s Final Analysis of the Declaration

An eloquent, spiritual, and forceful defense.

Coolidge’s Final Analysis of the Declaration – Matthew May

Next year, we will celebrate the Semiquincentennial of American independence.

The occasion will be replete with fireworks, massive celebrations across the nation, and – inevitably – speeches, speeches, and more speeches from politicians from every corner and of every stripe talking about the true meaning of the Declaration of Independence.

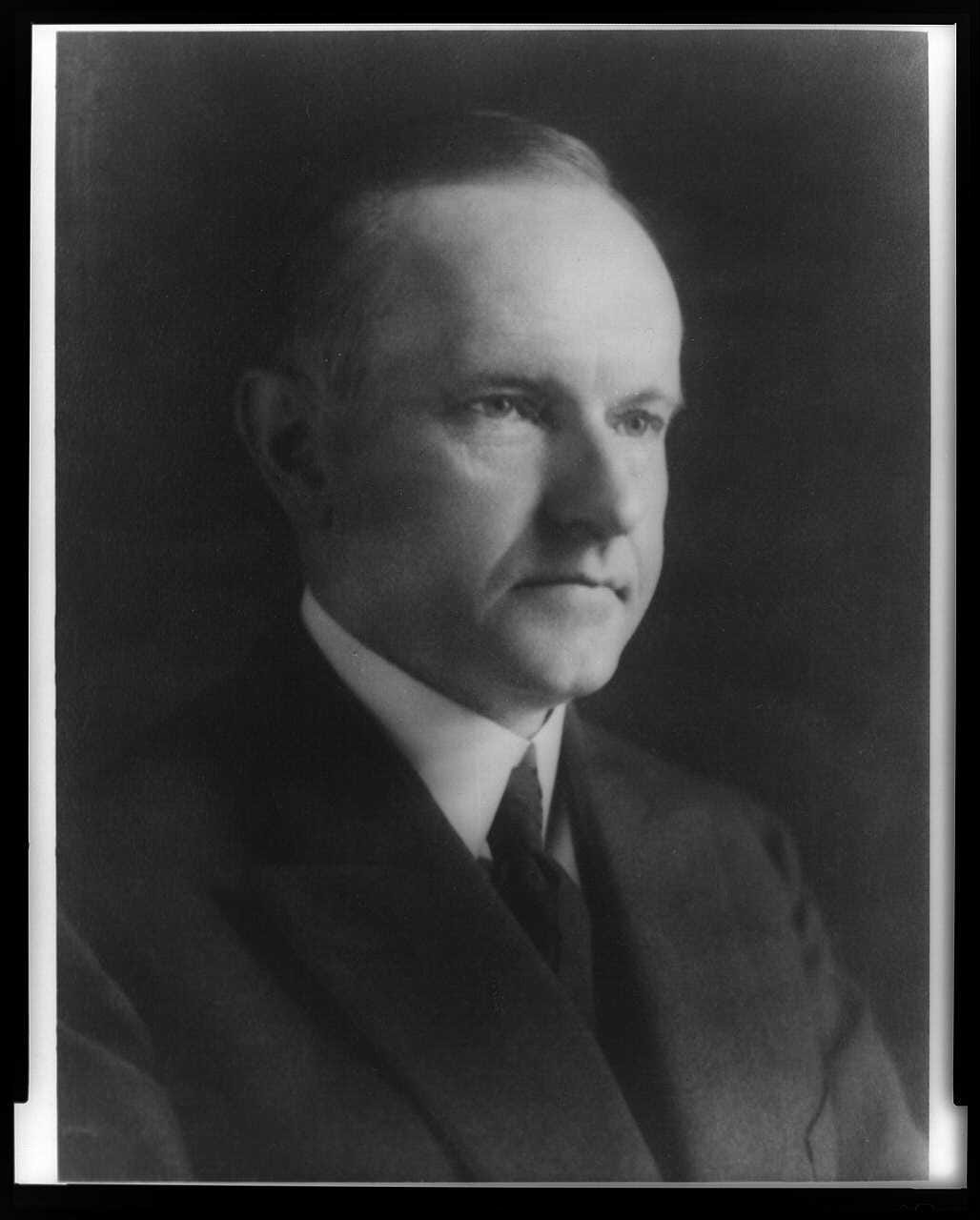

None will come close to the standard set by then-President Calvin Coolidge during the Sesquicentennial celebration of Independence Day and his address delivered in Philadelphia on July 5, 1926 (the Glorious Fourth fell on a Sunday that year, and a day of rest was observed).

It would be difficult to imagine a contemporary President delivering such an eloquent, spiritual, and forceful history, description, and defense of the Declaration and the American ideal.

In our day of general attention-deficit-disorder, few would wish to sit through an address of over 4,400 words – riveting though it may be and somewhat ironic in that it was delivered by the most taciturn of men. Perhaps out of necessity, White House speechwriters craft accordingly.

Also, given the self-regard exhibited by our most recent Presidents, it would be odd (though refreshing) to hear a speech that lacks the first-person pronoun, which is unleashed so much that transcribed presidential addresses resemble box scores of games featuring multiple one-run innings. The world is very different now.

When Coolidge took the rostrum and began to speak in what one biographer called “a small reedy voice…with precise New England pronunciation”, ideas of the so-called Progressive era still held significant sway. The Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, many “influencers” of the day argued, had run their course – the rapid technological and sociological advances had passed those fading documents by.

Furthermore – as rings all too familiar – the arresting phrase from the Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal” was not an example of words that should be etched in stone, but a hypocritical farce. Yet Coolidge knew the origin of things and understood that the Declaration was created by astonishingly brilliant yet imperfect men. As he said:

“We live in an age of science and of abounding accumulation of material things. These did not create our Declaration. Our Declaration created them. The things of the spirit come first. Unless we cling to that, all our material prosperity, overwhelming though it may appear, will turn to a barren scepter in our grasp. If we are to maintain the great heritage which has been bequeathed to us, we must be like-minded as the fathers who created it.“

Yet Coolidge reminded his audience in 1926 – and so it goes for Americans in 2025 – that maintaining and upholding the American ideal is the responsibility of the American people:

“It is a declaration not of material but of spiritual conceptions. Equality, liberty, popular sovereignty, the rights of man - these are not elements which we can see and touch. They are ideals. They have their source and their roots in the religious convictions. They belong to the unseen world. Unless the faith of the American people in these religious convictions is to endure, the principles of our Declaration will perish. We can not continue to enjoy the result if we neglect and abandon the cause.”

In George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, the character Winston Smith perceptively notes that the most powerful writing tells you what you already know. Such was the case for the Declaration of Independence, and Coolidge’s defense of it, much of which has a timeless quality born of his classic schooling and his own engagement with serious ideas:

“Amid all the clash of conflicting interests, amid all the welter of partisan politics, every American can turn for solace and consolation to the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States with the assurance and confidence that those two great charters of freedom and justice remain firm and unshaken. Whatever perils appear, whatever dangers threaten, the Nation remains secure in the knowledge that the ultimate application of the law of the land will provide an adequate defense and protection.”

Perhaps the most powerful part of Coolidge’s address was his final analysis of the Declaration, which could just as easily be considered the final analysis of the Declaration. Perhaps you will agree with the latter assertion after reading the following remarkable string of sentences that emphatically explains American principles:

“About the Declaration there is a finality that is exceedingly restful. It is often asserted that the world has made a great deal of progress since 1776, that we have had new thoughts and new experiences which have given us a great advance over the people of that day, and that we may therefore very well discard their conclusions for something more modern. But that reasoning can not be applied to this great charter. If all men are created equal, that is final. If they are endowed with inalienable rights, that is final. If governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed, that is final. No advance, no progress can be made beyond these propositions. If anyone wishes to deny their truth or their soundness, the only direction in which he can proceed historically is not forward, but backward toward the time when there was no equality, no rights of the individual, no rule of the people. Those who wish to proceed in that direction can not lay claim to progress. They are reactionary. Their ideas are not more modern, but more ancient, than those of the Revolutionary fathers.”

The whole of Coolidge’s educated, erudite, and elegant summation of the meaning of the Declaration of Independence – which is no less than the meaning of the United States of America – is well worth revisiting. Anything resembling it will unlikely be heard again, though it should be the resounding crescendo of every Independence Day for as long as the republic endures.

Read it all, rejoice in it, and recommit – every day, not just once each July – to living up to the principles of the Declaration of Independence, and making sure that your government does, too.